Using polyfitGC(), predict() and plot()

Preliminaries

The function polyGC() is a starter-tool for polynomial regression, when you think that the relationship between two numerical variables is not a linear one. It’s only a starter-tool: by the end of the course, or in later statistics courses, you will move on to R’s function lm(), which not only supports polynomial regression but also allows you to work with more than one explanatory variable and which provides additional useful information in its output. Also, in lm() the explanatory variable(s) can even be factors!

The function (and some of the data) that we will use comes from the tigerstats package, so make sure that it is loaded:

require(tigerstats)In this tutorial we will work with a couple of data sets: mtcars from the datasets package that comes with the basic R installation and RailTrail from the package mosaicData, so make sure you become familiar with them. The following commands may be helpful in this regard:

data(mtcars)

View(mtcars)

help(mtcars)For RailTrail:

require(mosaicData)

data(RailTrail)

View(RailTrail)

help(RailTrail)Formula-Data Input

Like many R functions, ployGC() accepts formula-data input. The general command looks like:

\[ployGC(response \sim explanatory, data = DataFrame, degree=DesiredDegree)\]

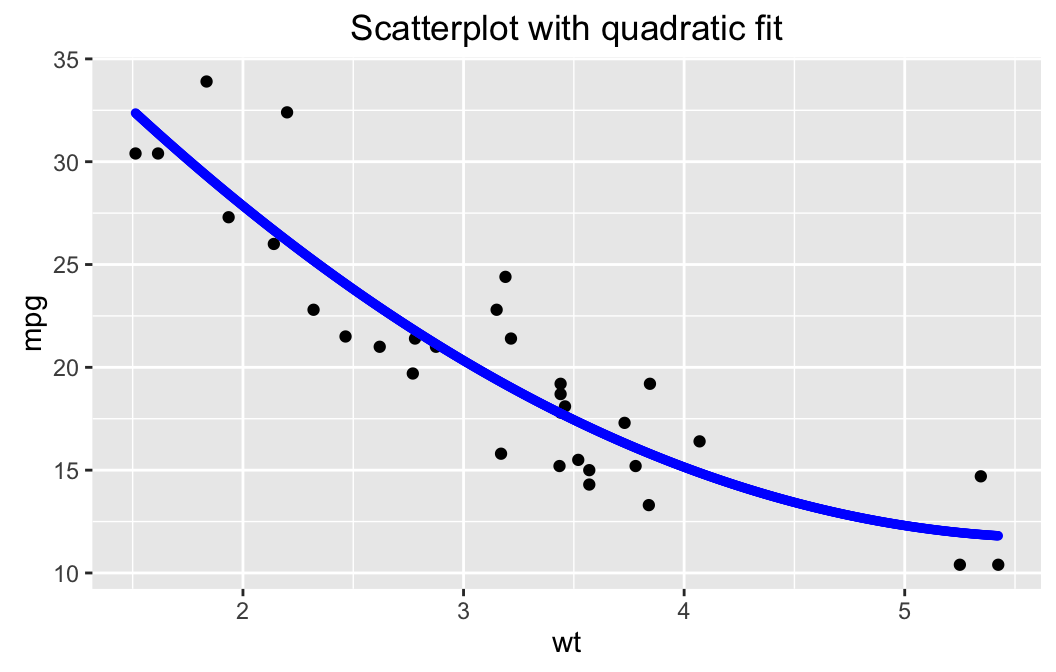

If you are interested in studying the relationship between the fuel efficiency of a car (mpg in the mtcars data frame, measured in miles per gallon) and its weight (wt in mtcars, measured in thousands of pounds), then you can run:

polyfitGC(mpg ~ wt, data = mtcars, degree=2)## Polynomial Regression, Degree = 2

##

## Residual Standard Error: s = 2.6506

## R^2 (unadjusted): R^2 = 0.8191

Setting the degree argument to 2 means that we want to fit a second-degree polynomial (a parabola) to the data.

The output to the console is rather minimal. You get:

- the residual standard error \(s\). As a rough rule of thumb, we figure that when we use the fitted polynomial to predict the fuel efficiency of a car from its weight, that prediction is liable to be off by about \(s\) miles per gallon, or so.

- the unadjusted \(R^2\). We see here that about 82% of the variation in the fuel efficiency of the cars in the data set is accounted for by the variation in their weights. since \(R^2\) is fairly high, it seems that weight is a fairly decent predictor of fuel efficiency.

By default, a graph is provided. If you don’t wish to see it, just use:

polyfitGC(mpg ~ wt, data = mtcars, degree=2,graph=FALSE)Prediction

When the value of the explanatory variable for an individual is known and you wish to predict the value of the response variable for that individual, you can use the predict() function. Its arguments are the linear model that is created by polyGC(), and the value x of the explanatory variable.

If you think that you might want to use predict(), you may first want to store the model in a variable, for example:

WeightEff <- polyfitGC(mpg ~ wt, data = mtcars,degree=2)Then if you want to predict the fuel efficiency of a car that weights 3000 pounds, run this command:

predict(WeightEff, x = 3)## Predict mpg is about 20.33,

## give or take 2.709 or so for chance variation.We predict that a 3000 pound car (from the time of the Motor Trend study that produced this data) would have a fuel efficiency of 20.33 mpg, give or take about 2.709 mpg or so. The “give-or-take” figure here is known as the prediction standard error. It’s a little bit bigger than the residual standard error \(s\), and as a give-or-take figure it’s a bit more reliable. (By the way, it also differs for different values of the explanatory variable.)

You can also get a prediction interval for the response variable if you use the level argument:

predict(WeightEff,x=3,level=0.95)## Predict mpg is about 20.33,

## give or take 2.709 or so for chance variation.

##

## 95%-prediction interval:

## lower.bound upper.bound

## 14.789863 25.869300The interval says you can be about 95% confident that the actual efficiency of the car is somewhere between 14.79 and 25.87 miles per gallon.

Diagnostics

You can also perform some simple diagnostics using the plot() function:

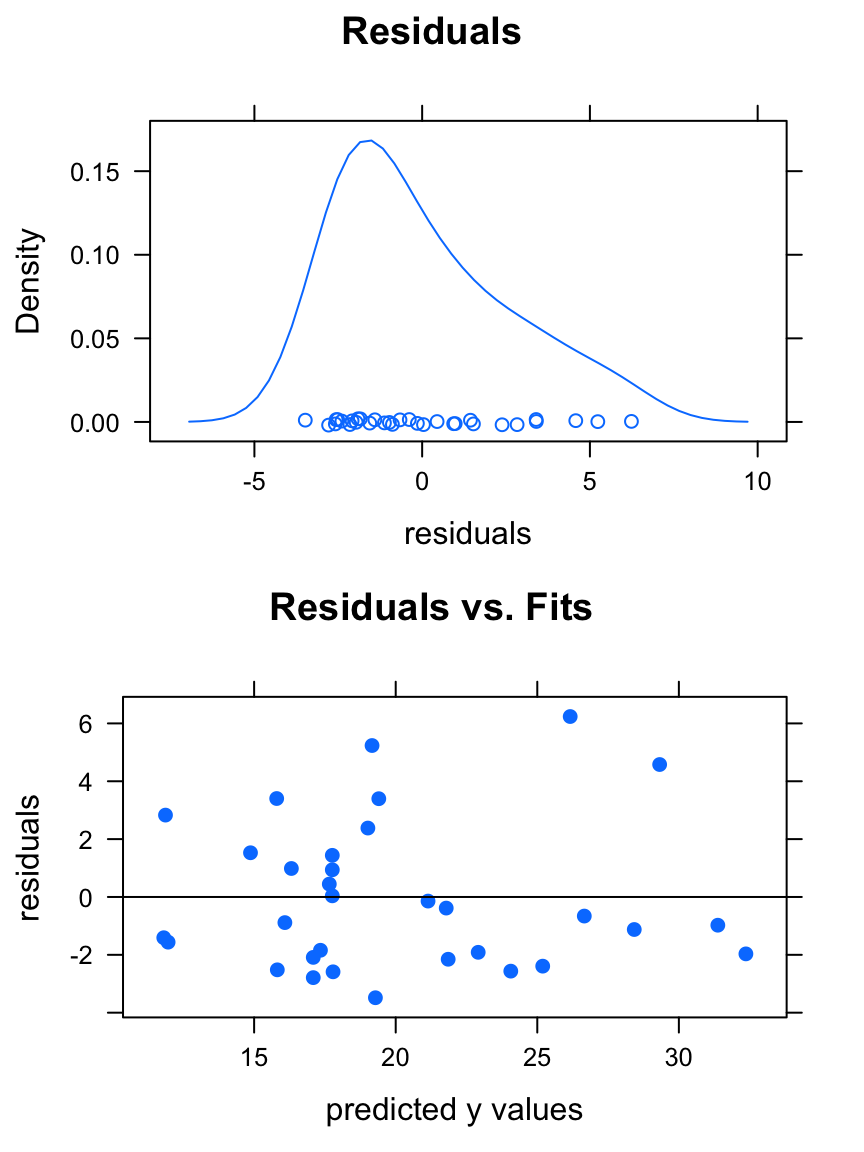

plot(WeightEff)

You get two graphs:

- a density plot of the residuals. If the distribution of the residuals is roughly bell-shaped, then the 68-95 Rule says that:

- about 68% of the residuals are between \(-s\) and \(s\);

- about 95% of the residuals are between \(-2s\) and \(2s\).

- A plot of the residuals vs, the

fitted\(y\)-values (the \(y\)-coordinates of the points on the original scatter-plot). If the points exhibit a polynomial relationship with about the same amount of scatter all the way along the polynomial fit, then this plot will look like a random cloud of points

If you plan to use your polynomial for prediction and to rely upon the prediction standard errors and prediction intervals provided by the predict() function, then the residuals should be roughly bell-shaped, and the plot of residuals vs. fits should look pretty much like a random cloud.

In this case, the plots indicate that we can make fairly reliable predictions from our linear model, although I would be a bit concerned about the right-skewness of the residuals.

Further Checks

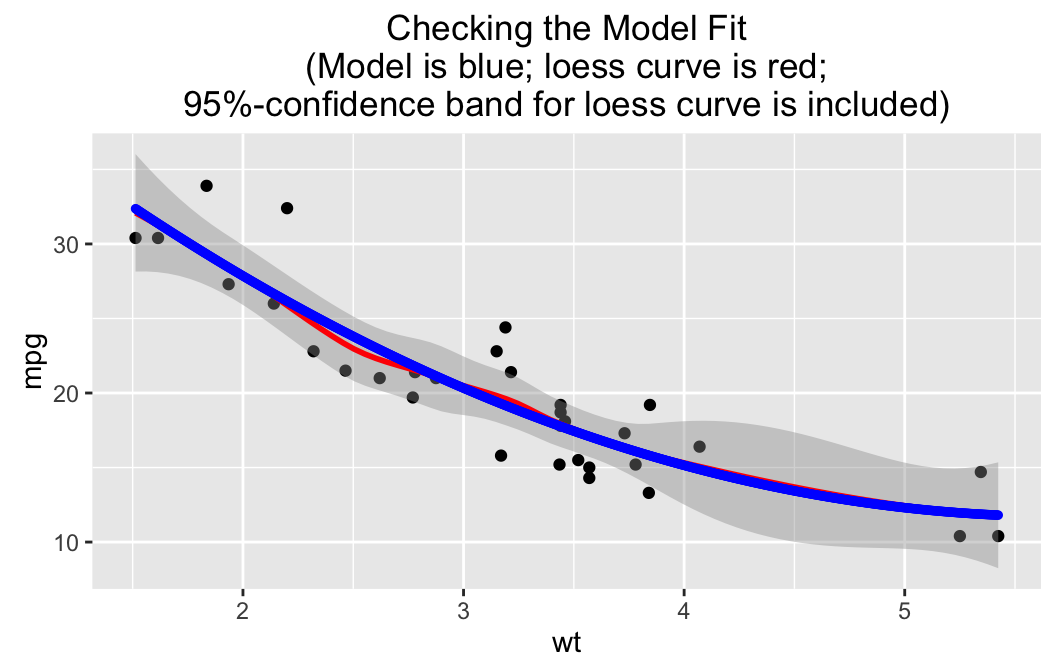

Another nice way to check whether your fit is appropriate to the data is to use the check argument for lmGC(). Let’s perform a check on the WeightEff model:

polyfitGC(mpg ~ wt, data = mtcars, check = TRUE)## Polynomial Regression, Degree = 2

##

## Residual Standard Error: s = 2.6506

## R^2 (unadjusted): R^2 = 0.8191

The second-degree fit is graphed, but there is also a “loess” curve, a smooth curve that does not make much assumption about what kind of relationship produced the data in question. Surrounding the loess curve is a 95%-confidence band: based on the data we are pretty sure that the “real” relationship between wt and mpg is some function with a graph that lies within the band.

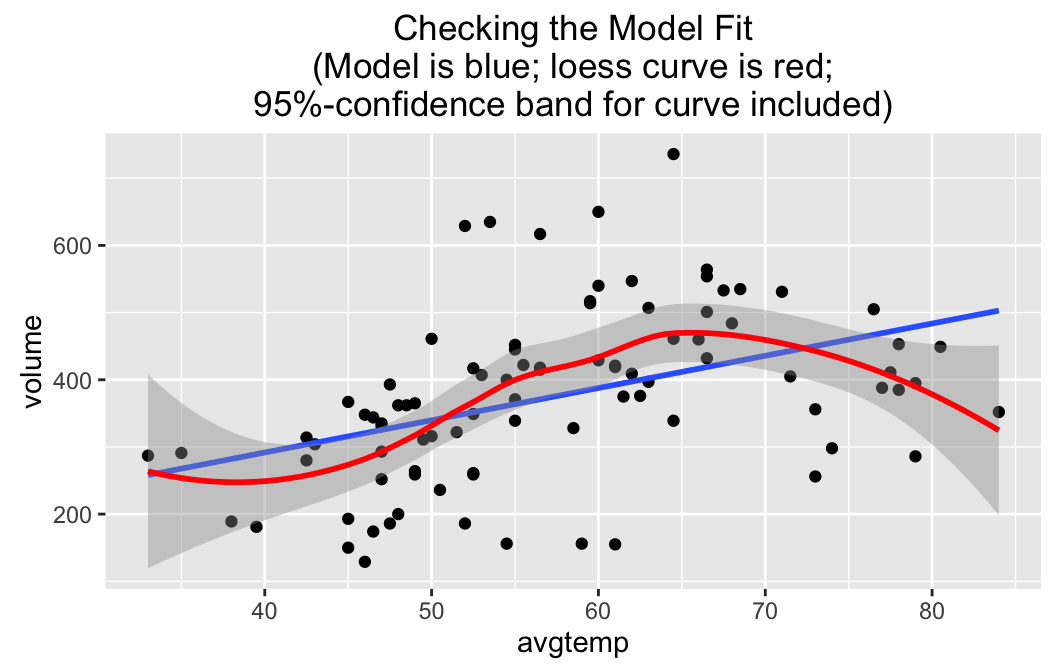

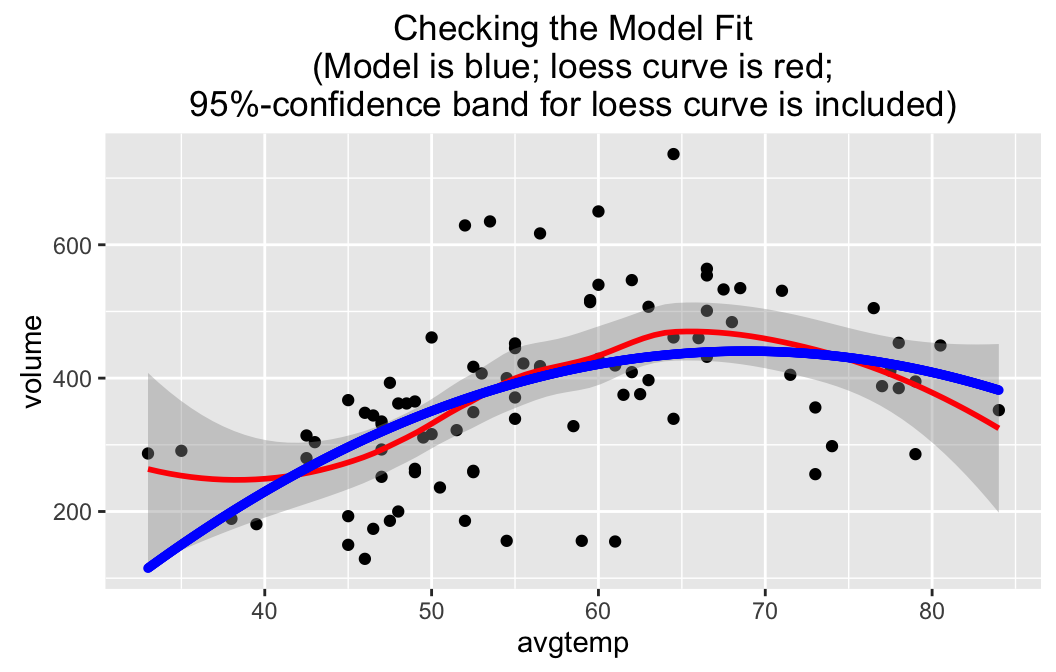

As another example , consider a check on a linear model for the relationship between volume (number of bikes on the trail) and avgtemp (average temperature for the day) in the RailTrail data frame:

lmGC(volume~avgtemp,data=RailTrail,check=TRUE)##

## Linear Regression

##

## Correlation coefficient r = 0.4269

##

## Equation of Regression Line:

##

## volume = 99.6023 + 4.802 * avgtemp

##

## Residual Standard Error: s = 115.9202

## R^2 (unadjusted): R^2 = 0.1822

Note that the regression line wanders a bit outside the band, so a linear fit probably is not quite adequate–especially for days with higher temperatures, when people may forsake bicycle trials for other warm-weather activities such as swimming. At very high temperatures outside the range for which we have data, volume should be low, so the “real” relationship is probably quite curvilinear.

Perhaps we should learn how to fit something other than a straight line to data! How about a second-degree polynomial?

polyfitGC(volume~avgtemp,data=RailTrail,check=TRUE)## Polynomial Regression, Degree = 2

##

## Residual Standard Error: s = 110.0599

## R^2 (unadjusted): R^2 = 0.2712

The parabola doesn’t wander outside the 95%-confidence band around the loess curve, and frankly it makes more sense than the loess curve at lower temperatures. (At the left end the loess curve appears to have been rather strongly influenced by two points.)

There is much more to say about regression and prediction: for instance, we would like to take into account more than just one explanatory variable. Look forward to learning more in the future about the full power of regression with R’s lm() function!